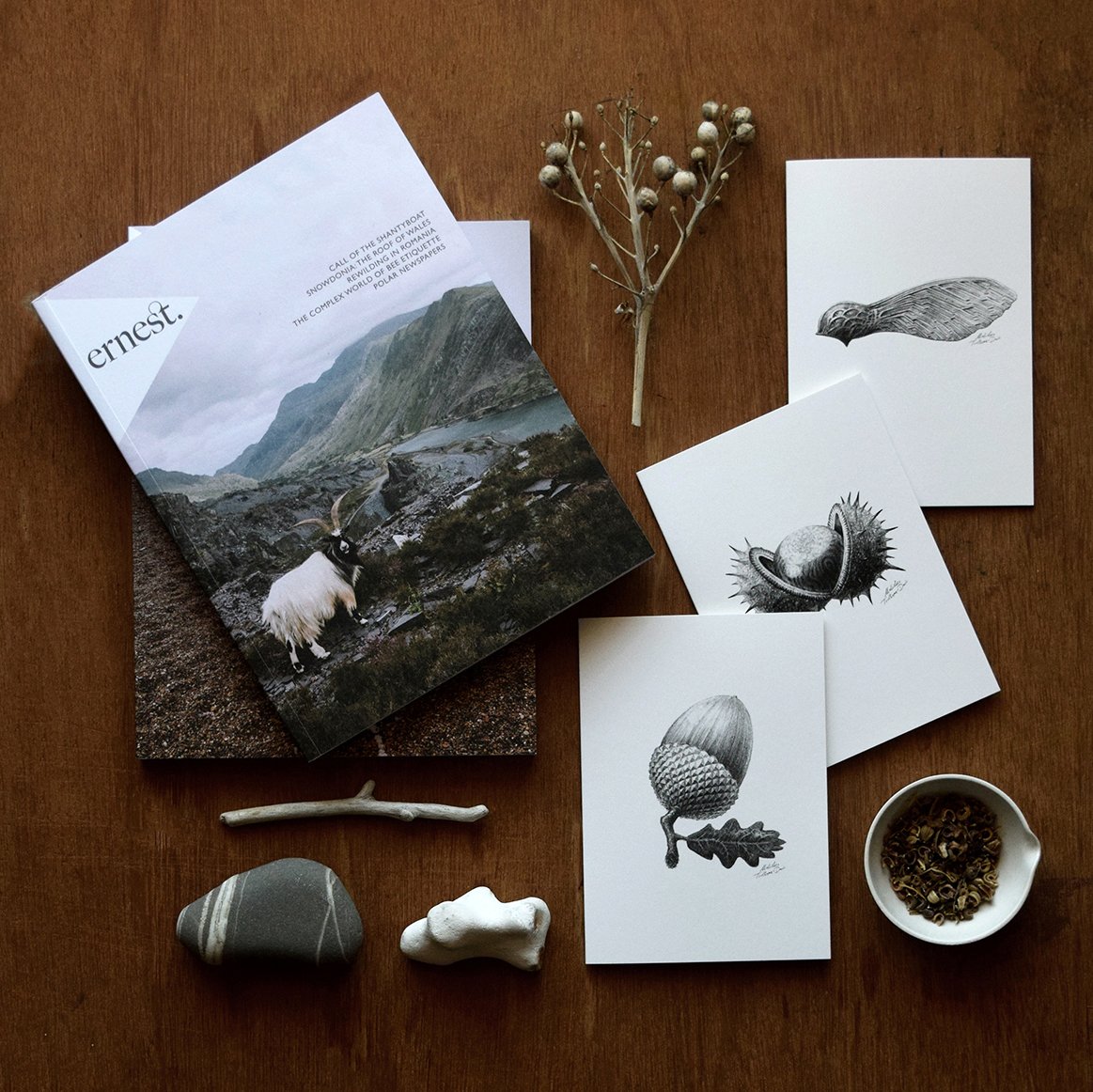

What would the “perfect” horse chestnut or pine cone look like? Inspired by his walks in the South Downs, artist Malcolm Trollope-Davis sought to answer this question by keenly observing growth patterns in the minutiae of the natural world around him. He invites us into his Brighton studio to tell us more…

Malcolm Trollope-Davis’ original ‘Technature’ drawing of a horse chestnut

Malcolm, we love the beautiful simplicity of your Technature designs. What inspired you to create them?

This may sound strange but what triggered the concept was spending most of my adult life illustrating, creating, using and being immersed in computer technology. It’s an unavoidable side of my professional life as it allows you to create exceptionally detailed and precise work. I believe our exposure to computers affects the way we think and feel. So accustomed to seeing perfectly created shapes, I started looking for them in nature during my walks in the South Downs.

Of course "perfect" shapes and forms are hard to find in nature (that's the beauty of nature), but I began to observe acorns and other seeds and attempted to recreate their growth code. I counted the spikes on a horse chestnut and studied the arrangement of its pattern. In my recreation of this I drew a perfect spike protruding from its casing every 45 degrees, evenly spaced from each other. Of course you’d never find a chestnut as perfect as that in nature but I guess I was curious to see what it would look like. For my acorn, I gave it a sort of machine-tooled cup pattern. The end results seemed to be a good balance of technical and nature, hence the ‘Technature’ title of my collection.

Do you often turn to nature for inspiration?

More and more, the older I get! There's something rewarding about recreating the things surrounding you. Perhaps recreating it gives you an excuse to just stand still and take the time to really observe it.

For you, what is the most beautiful thing in nature?

I think the freshness and growth. As a human and certainly an artist, it’s important and therapeutic to have a desire to grow and progress (and hopefully improve). Nature never stops doing this and I find that reassuring as I consider myself part of nature. Also, I’m particularly drawn to the patterns you can see in the spread of branches and the number of points on a leaf.

Your Brighton map is a wonder. Can you please tell us about the journey of making this?

I think the map was a project that fell under that ‘describe your surroundings’ concept, but taking the detail to a very high degree. To all intense and purposes, it looks as though you can see every building in the city and far beyond to Shoreham and Worthing. It’s the result of an incredibly painstaking editing process. To give you an example, in a street of 20 identical houses I may only illustrate 10. Why do this? Well, by using this same process all over the map, house by house and street by street, you can make the houses a little bit bigger. All the rooftops and building shapes have been observed and carefully recreated, but because their size is bigger the viewer can decipher the visual information much more clearly than, say, in an aerial photograph. Resident who live on that street can still say “that must be my house” and hopefully buy an art print! Adding moments in history and famous Brightonians from the past also makes the map more engaging and friendly.

Are there any other projects you're currently working on?

Yes, too many. If I’m not careful they can get in the way of paid work. I’ve just finished writing a children’s book. I’ve been illustrating them for other people for years but had this idea running around in my head for a long time. My partner Dörte suggested I just sit down and get it down on paper. I haven’t had it published yet but the few guinea pigs who’ve been kind enough to read the manuscript have been extremely positive. One 12 year old (who shall remain nameless) finished all 160 pages in just a few days. Other than that, I have a folder with over 50 creative concepts ready to roll, from board games to TV show concepts. I just need more time!